This view, I believe, represents the mainstream contemporary beliefs of most people who theorize about research methodology. It fully accepts the increasingly common view among scholars in the 20th century that anything simple must be guided by ideology rather than by a "true" understanding of reality, by "careful" consideration of alternative viewpoints, or by a "diligent" attention to complexities. The implication is that those who propose simple theories are themselves simple-minded, and most likely motivated by something other than research, for example by religious beliefs or wishful thinking.

There are, of course, people on the other side of this debate: people who believe that there are simple, unitary, and strikingly clear explanations for reality, and that those who insist on convoluted theories are simply caught up in their own academic gobbledygook and a refusal to acknowledge what they know in their hearts (if only they'd listen to them) to be true.

(Need I make explicit allusion here to one example of how this debate plays out; namely, between the policy makers in the current administration who insist that all educational programs be supported by double-blind controlled experiments--i.e. by simple data and analysis--and those post-modernist theorists and methodologists who insist that much of reality cannot possibly be understood using such simple methods? Well, I will make such an allusion anyway!)

While--as a tweedy intellectual academic myself--I usually side with the post-modernist people who seek complexity and convolution, one comment of Aaron's caught my attention. He wrote:

(One key limitation of this picture is the straightness of the different axes. In actuality, as one moves out along the axis of “texture,” for example, one necessarily moves closer to both other axes, since teasing out complexities will increasingly require reference to the writings of others and to unexplained aspects of the context under examination. Thus, imagine that all of these axes curve towards each other (which I don’t know how to do in my simple drawing program.)

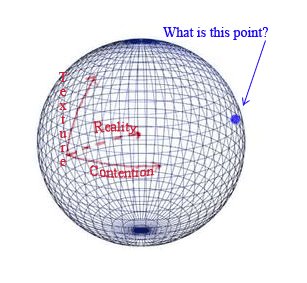

I have spent the last few days thinking about what this schematic would look like if the axes curved toward one another as Aaron describes. It's difficult to visualize (mainly becuase there are THREE axes--hence a three-dimensional space: hard to visuallize, let alone draw. But one thing is clear: if the axes curve toward one another, then eventually, at some point "out there," they would intersect.

Because I can't draw anything truly three-dimensional, I've chosen to "sort of" represent what this would look like with curved axes. I've drawn two of the axes on the surface of a sphere, with the third axis sort of tending toward the center of the sphere. Then, I've imagined that the three axes eventually intersect at some point on the other side of the sphere. Thus:

Because I can't draw anything truly three-dimensional, I've chosen to "sort of" represent what this would look like with curved axes. I've drawn two of the axes on the surface of a sphere, with the third axis sort of tending toward the center of the sphere. Then, I've imagined that the three axes eventually intersect at some point on the other side of the sphere. Thus:What this leads me to imagine is, What the heck is that point of intersection on the other side? Is it, perhaps, the point-of-view of someone who holds that the best theory is one in which texture, contention, and reality finally come together into a grand theory that supercedes all of the silly vain attempts of intellectuals to strive toward more and more complexity, that is, the unified field theory (if you will) that embraces unity, simplicity, and universality?

What if Aaron's notions of sophistication are only half the story, that once a theory has incorporated all that complexity and contention and convolution that eventually it evolves into something truly elegant? Maybe "sophistication" cannot be measured purely by complexity? Or, maybe what Aaron is really saying is that he wants his STUDENTS to embrace complexity so that they eventually learn to listen to their hearts?

Occam's Razor, anyone?

No comments:

Post a Comment