--Gouldner (1979, p. 8)

“Because all concepts are approximations, this does not make them ‘fictions’. . . [; in fact,] only . . . concepts can enable us to ‘make sense of,’ understand and know, objective reality . . . [; at the same time, however,] even in the act of knowing we can (and ought to) know that our concepts are more abstract and more logical than the diversity of that reality.”

--Thompson (2001, p. 461).

“Reality” is too complex to fully capture in abstractions. Every study selects particular aspects of the world to emphasize, necessarily leaving the rest in a shadowy background. In other words, we must choose what is generally called a “theoretical framework” to guide our analysis. This choice helps determine what we “see” in our data—how we make sense of what happened in a particular context. In fact, one of the first questions a dissertation advisor will often ask a new doctoral student about their dissertation is, “what’s your theoretical framework?” Despite the importance of this choice, however, it is a process that is rarely examined in the literature.

It seems to me that questions about the genesis of theoretical frameworks are central to the place of foundations in educational scholarship. Foundations classes (in sociology, philosophy, history, etc.) represent one of the few places in graduate education where students are likely to encounter a range of different and contrasting theories.

In my limited experience, graduate students often acquire theoretical frameworks in extremely problematic ways. The most common source of a framework is probably in the work of one’s advisor. In my school, there was a recent spate of dissertations using Bandura’s theory of “self efficacy,” reflecting the interests of a small group of professors. I imagine other graduate students walking up to a Borgesian bookcase of theories, skimming through them until one strikes them as useful: “Hmm . . . . Barthes? No. Bakhtin? No. Bernstein? No. Oh, Bourdieu! Okay, good.” I rarely see early career scholars think in any sophisticated fashion about the plusses and minuses of particular theoretical frameworks, about what each illuminates and obscures (although this may be a product of my particular university).

Let me propose, speculatively, a simple schematic theory of how scholars should construct theoretical frameworks. It seems to me that there are three key axes that determine whether one has a more or less sophisticated approach to theory in the context of a study.

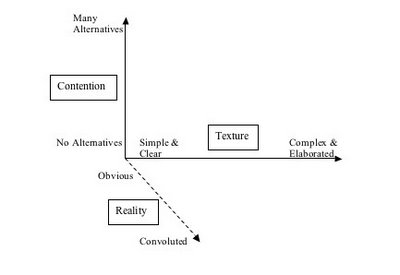

Let me propose, speculatively, a simple schematic theory of how scholars should construct theoretical frameworks. It seems to me that there are three key axes that determine whether one has a more or less sophisticated approach to theory in the context of a study.--The first axis I call “texture.” As one moves out along this axis, one becomes increasingly conscious of the internal tensions and complexities of a particular theory. Depending on the internal sophistication of a particular theorists, there may be real limits on how far one can move in this direction.

--The second axis I call “contention.” As one moves out along this axis, one increasingly grapples with critiques of a particular theory and, in the farther regions, begins oneself to consider the ways other theories might complicate the conceptualizations of a particular theory.

--The third axis I call (with apologies to postmodernists) “reality.” Moving out along this axis one becomes increasingly sensitive to the internal texture of the data one is examining, of the aspects of the world that are and are not included, and of the alternate ways one might conceptualize relationships between different aspects.

Of course, this graphic is much too simple—but like all theories I think it illuminates something important about the nature of academic writing and the operation of theoretical frameworks. (One key limitation of this picture is the straightness of the different axes. In actuality, as one moves out along the axis of “texture,” for example, one necessarily moves closer to both other axes, since teasing out complexities will increasingly require reference to the writings of others and to unexplained aspects of the context under examination. Thus, imagine that all of these axes curve towards each other (which I don’t know how to do in my simple drawing program.)

Within this schematic, there are different ways that one could be sophisticated about one’s use of theory. One could look at one particular theoretical framework (or theorist) in detail, exploring its complexities and tensions. One could address the broad range of contrasting perspectives that might reveal limitations in one’s theory—perhaps leading one to draw from more than one theory at the same time. And one could take a focused “grounded theory” approach where one seeks to understand the richness of a particular situation or data set. Each of these choices, and combinations of them, place one at a different point in this three-dimensional space.

(Of course, as Gouldner points out, above, moving too far out along an axis can lead one away from understanding into incoherence.)

I want to argue, then, that scholars who find themselves near the vertex are generally those with inadequate theoretical frameworks. These are scholars who:

--draw from a single simplistic theory;

-- tend to gloss the critiques of others; and

-- generally don’t look beyond the aspects of the world that their preferred theory emphasizes.

Scholars like this have probably either accepted without much critique the perspectives of their advisors, or have chosen theories that reflect conceptions they brought with them to a particular topic in the first place. (In a Gadamerian sense, their theoretical choices have neither helped them identify nor put tension on their own prejudgements).

What does this mean for graduate education?

In the first place, I think it indicates that we should insist that even students who are not focused on “theory” have a relatively sophisticated understanding of the internal texture of their theoretical framework they have chosen.

Second, it seems to imply that acquiring a sophisticated understanding of a single theory is not sufficient. It seems to me that we should insist that students achieve an understanding of at least one other different theoretical perspective that can put tensions on the first. It is only possible to understand the limitations of one framework when one examines this from the perspective of another. Those of us with experience with a range of frameworks can point them towards an alternative that might usefully challenge their current perspective.

Finally, we should be suspicious when students’ studies indicate that a particular simple theoretical framework can be used to explain a particular data set with no difficulties. Reality is _never_ accurately represented in such a simplistic way, and when scholars imply it can be they fundamentally distort our ability to understand the world and to apply the findings that emerge from a particular study to the always somewhat different complexities of a different context.

The issue, here, is the _minimum_ we should expect from doctoral students before we are willing to certify that they are able to adequately conduct research, and what role foundations professors should play in this process.

Gouldner, A. (1979). The future of intellectuals and the rise of a new class. NY: Seabury Press.

Thompson, E. P. (2001). The essential E. P. Thompson. NY: The New Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment